Discussion Questions and Document Links

| Date Posted |

Questions/Assignment

|

| Aug. 24, 1999

|

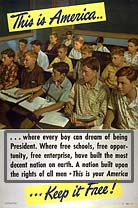

A term we will use occasionally in this course is

"American exceptionalism," the commonly-held belief that the United States is

the most unique (and uniquely fortunate) nation in the history of the world, that it is an

exception to the typical problems that have plagued other places (for example, Russia)

throughout history. Is there any truth to American exceptionalism? What, if anything, do

you think makes the United States, and the American experience generally, unique in the

world and in history? |

| Aug. 31, 1999

|

This question has two major sections and several

subquestions. For purposes of the bulletin board, you may respond to any or all of the

parts, though in section you should try to cover more of it:

-- First, read the biblical texts that are the basis of the Christian doctrine of original

sin, roughly Genesis

2:4 to 4:16. (You may want to look at the first four books of Genesis in their

entirety, which adds up to only about 7 pages.) Did Early Modern Europeans interpret these

passages correctly in developing their notions of the innate depravity of human beings?

What kind of society and political structure would be likely to develop based on this idea

of original sin? Leaving aside the religious questions involved, is there anything to be

said in favor of the idea as original sin as a basis for ordering a society?

-- Second, read this brief document recounting the Iroquois

story of the founding of their confederacy. Compare and contrast this founding story

with the one in Genesis. How would a society and political structure based on this story

differ from the European one? Where would you rather live? (You may also bring in the

material on American Indian politics in Nash & Schultz, chap. 2) |

| September 7, 1999

|

Think about the similarities and differences between the colonization projects at Virginia

and Massachusetts (including the Plymouth Colony), in terms of their intentions, personnel, and results (social,

political, or economic). What were some key institutions

and/or events that reflected these similarities and differences? Where would you rather

have lived, as a colonist? Who would you rather have dealt with as an

American Indian, or would it have made any difference? In which colony

(Virginia or Massachusetts) can you more clearly see origin points (if

any) for aspects of later American culture?

Before answering this question, make sure you have done your reading

for this week, Goldfield,

et al., American Journey,

Ch. 2; Nash & Schultz, Chs. 3

& 4. In addition, here are some documents to help you with

these questions. All are helpful, but required readings are listed in BOLD

type.

Sketches

from the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities web site: The Virginia Company of London, Captain John Smith, John Rolfe, Pocahontas.

Perhaps the most

interesting documents on this site are these lists of colonists at Jamestown, noting

their occupations. Also helpful are this "Brief History of Jamestown"

and this chronology. Sketches

from the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities web site: The Virginia Company of London, Captain John Smith, John Rolfe, Pocahontas.

Perhaps the most

interesting documents on this site are these lists of colonists at Jamestown, noting

their occupations. Also helpful are this "Brief History of Jamestown"

and this chronology.

John

Smith was considered a harsh ruler by many of the Jamestown colonists, but look

what happened after Smith left.

To hold things together after that, these harsh

laws were passed. John

Smith was considered a harsh ruler by many of the Jamestown colonists, but look

what happened after Smith left.

To hold things together after that, these harsh

laws were passed.

Compare

the First

Charter of the Virginia Company, especially its sections regarding religion, with this

1661

report to the Bishop of London on the actual state of religion in the colony. Compare

the First

Charter of the Virginia Company, especially its sections regarding religion, with this

1661

report to the Bishop of London on the actual state of religion in the colony.

The

classic statement of Puritan intentions and aspirations for the Massachusetts Bay Colony

is "A Modell of Christian

Charity" (1630) , by the first governor, John Winthrop. The key passages

appear near the end of the document. Before assuming that the Puritans

migrated for religious freedom, read Winthrop's

views on how much and what kind of liberty he would allow in Massachusetts

Bay. Also, glance over The Charter of Massachusetts

Bay: 1629 and compare it with the Virginia charter. The

classic statement of Puritan intentions and aspirations for the Massachusetts Bay Colony

is "A Modell of Christian

Charity" (1630) , by the first governor, John Winthrop. The key passages

appear near the end of the document. Before assuming that the Puritans

migrated for religious freedom, read Winthrop's

views on how much and what kind of liberty he would allow in Massachusetts

Bay. Also, glance over The Charter of Massachusetts

Bay: 1629 and compare it with the Virginia charter.

|

September 14, 1999

|

Southerners before and after the Civil War often defended slavery (and later, segregation) as the basis of a "way of life" that Southerners had led since the founding of the colonies.

(Refer to your reading in Stampp to see what I mean.) Is this true? What was the most important cause for slavery becoming the South's dominant labor system? One theory holds that racism, European prejudice against darker-skinned peoples, was the main cause. Does this make sense to you? (Some historians have felt that it does not make sense.) If you agree that racism was the main cause of slavery, what do you make of the fact that racism has continued to be terrible problem more than 130 years after slavery was abolished? Before answering look at these brief documents on the evolution of the Virginia labor system: letters on the experiences of

a male indentured servant and

a female indentured

servant, the changing laws of Virginia regarding children and

marriage, the reaction of Virginia planter William Byrd to a proposal to ban slavery from the new colony of

Georgia, and an African's memories of the "middle passage" to slavery in

America. |

| September 21, 1999 |

What were the most significant ways in which the Middle Colonies (focus on New York and/or Pennsylvania) were different from Virginia and Massachusetts? Is it possible that New York and Pennsylvania, though less aggressive than the South or New England in claiming to define Americanism, actually contributed more to later American culture than the more extreme colonies did? |

| October 5, 1999

|

Make sure you have read through chapter 5 in your textbook before trying to answer this question.

As citizens of the United States, we naturally tend to side with the American colonial protesters when reading about the American Revolution. But is there anything to be said for the British side of the equation? The British government did not expect such controversy over their reforms of the empire and efforts to generate some tax revenue in the colonies. They saw the Stamp Act, Townshend Acts, etc., as moderate, reasonable, necessary measures that were well within the government's rights and perfectly just in any case. The colonists saw these same measures as intolerable acts of tyranny, part of a conspiracy to take away the colonists' rights and reduce them to "slavery." In your opinion, who had the more reasonable and convincing position, the British or the Americans?

Here are some documents exemplifying the two positions. Reading them is

optional, but you will have to understand the general positions that they

outline:

COLONISTS

Daniel

Dulany, "Considerations," October 1765 Daniel

Dulany, "Considerations," October 1765

Resolutions

of the "Stamp Act Congress," 1765 Resolutions

of the "Stamp Act Congress," 1765

Benjamin

Franklin, Testimony Before Parliament on the Stamp Act, 1766 Benjamin

Franklin, Testimony Before Parliament on the Stamp Act, 1766

John

Dickinson, "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania," 1768 John

Dickinson, "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania," 1768

George

Washington's fears of a British Conspiracy George

Washington's fears of a British Conspiracy

BRITISH (looking for more)

Soame

Jenyns,

The Objections to the taxation consider'd, 1765 Soame

Jenyns,

The Objections to the taxation consider'd, 1765

The

Declaratory Act, 1766 The

Declaratory Act, 1766 |

October 12, 1999: Option A

Precursors of the Declaration:

Documents Relating to Jefferson, the Declaration, and

Slavery:

|

Probably most of you are

familiar with some of the words of the Declaration

of Independence, but now you should really read it, on the web or in

your textbook. How should we regard the document from the perspective of

200 years later? Does it give an accurate account of the American

colonies' problems with Great Britain? Was it really so original? (See

the optional documents listed at left for earlier statements that, some

historians claim, may have beaten Jefferson to the punch.) Finally,

what should we think of the Declaration and its statements about equality

in light of the fact that its author, Thomas Jefferson, was a large-scale

slaveholder, a committed racist, and (as has now been proven by DNA

testing) the father of many children by his slave Sally Hemings? (Given

a female slave's utter lack of choice in the matter of submitting to her

master's sexual advances, one could argue that Jefferson was little better

than rapist in this aspect of his life.) Can a document written by such

an author have any value for us? (DO NOT ASSUME THAT

ANY ANSWER IS THE RIGHT ONE. THESE ARE OPEN, DEBATABLE QUESTIONS.) The

documents listed to the left will help give you a deeper understanding of

Jefferson's views on slavery, and slaves' views the Declaration? |

| October 12, 1999: Option B

|

Historians and journalists have

long dismissed the early U.S. government operating under The

Articles of Confederation as ridiculously weak, inept, and unworkable.

Putting yourself in the shoes (and mind) of a person who lived through the

1760s & 70s, would there be anything you could say in favor of the

Articles? How would you have defended them against critics (such as the

advocates of the present US Constitution), who wanted some stronger form

of national government? |

Bonus

Question

(very optional)

Documents useful in answering this question

(optional):

|

One of the most tortured

historical debates of recent times centers around an argument, made by a

handful of determined historians and later picked up on by textbook

writers and documentary film-makers, that the American Indians

(specifically the Iroquois League) were an important influence on (or even

a major inspiration for) the political thought and constitutional

structure of the (white) American republic. The chief evidence for this

concerns some comments that Benjamin Franklin made at a time (just before

the French and Indian War) when he was promoting the idea of a defensive

union of the colonies that would still be part of the British empire. Read

Franklin's remarks (and his Albany

Plan of Union) and give your own view of the possibility that the Iroquois

provided the prototype for the United States. Even if you do not buy that

argument, can you see any ways that the Indians may have influenced

Euro-American political thought and government structure? Other helpful

documents are available on the left. |

| October 19, 1999

|

Read the U.S.

Constitution and think about the following questions:

1. One of the bitterest debates leading to the Civil War concerned

exactly who created the Constitution, and what was created. Most

southerners subscribed to the so-called "compact theory," which

held that the Constitution was merely an agreement among the states that

any state could pull out of or disobey when it felt that its rights were

being violated or left unprotected. (Compare this idea to the Lockean

standards for dissolving a government outlined in the Declaration

of Independence.) Most northerners came to believe in a different

theory, that the Constitution had been adopted by the people of the whole

United States and created a single, consolidated national government

("the Union") that no state had any right to oppose or

leave. Which theory was a more accurate interpretation of the

framing and ratification of the Constitution?

2. The radical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison became infamous

before the Civil War for calling the Constitution a "covenant with

death" and an "agreement with Hell" because of the way the

protection of slavery was built into it. Garrison took to burning a copy

of the Constitution at anti-slavery rallies. Even many modern

historians argue that the Constitution was a pro-slavery document.

What do you think? Did Garrison and these later historians go too far in

condemning the Constitution, or was protecting slavery one of the

document's fundamental purposes? |

| October 26, 1999

|

Imagine that you are a voter or congressman during the 1790s. Whom would you have supported, Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists, or Thomas Jefferson and the Republicans? What particular position or idea would most influence your choice?

HELPFUL DOCUMENTS:

|

November 9, 1999

|

After you have completely read

chapters 9, 11, & (ideally) 13 in the AMERICAN JOURNEY, evaluate the

following statement: "Though it has very little hold over the

present national imagination, the War of 1812 is in fact one of the

critical turning points of American history, paving the way for or

actually causing numerous key developments in 19th-century American

life." Agree or disagree with the statement, using specific

examples from the text or lectures.

|

| November 16, 1999

|

Read "David Walker's

Appeal", along with William Lloyd Garrison's response to it

. If you were an African American (slave or free) in the 1820s, what strategy would you have favored in dealing with slavery: violence as advocated by Walker and practiced by Nat Turner; colonization to Africa; or peaceful "moral suasion" and political agitation as advocated by William Lloyd Garrison and black abolitionists less radical than David Walker, such as Frederick Douglass? From today's perspective, which strategy was most effective?

|

| November 30, 1999

To learn more about party system "founder" Martin Van

Buren (including numerous video clips), check the Van

Buren page on the C-SPAN

"American Presidents" website.

|

The party system is one of the most

unpopular institutions in the U.S. today. Increasing numbers of voters

claim to be independents, "nonpartisan" is a positive label,

crackpot billionaires and pro wrestlers have 100,000s of votes by bashing

the major parties, and even Democrats and Republicans often hide their

party affiliations in campaign advertising. Yet when the party system was

invented in the 19th century, it was considered by many Americans to be

one of the great political innovations in the history of the world, and

was copied in 100s of countries. (Others, including many radical

abolitionists and Christian reformers strongly disagreed.) What do you

think, looking at the role of parties in the 19th century? What positive

and negative contributions did the major national political parties

(especially the Democrats and Whigs) make before the Civil War? Chapters

10, 9, & 15 of AMERICAN JOURNEY should be most helpful in answering

this question.

|

|

![]()